TERMINAL IMAGINARIES: REFLECTIONS ON THE TACTICS OF PRACTICE

BY SEAN PURCELL

PhD Candidate

The Media School

BY SEAN PURCELL

PhD Candidate

The Media School

“I hate music

What is it worth?

Can't bring anyone

Back to this earth

The feeling of space

Between all of the notes

But I got nothing else

So I guess here we go”- Superchunk, “Me and You and Jackie Mittoo”

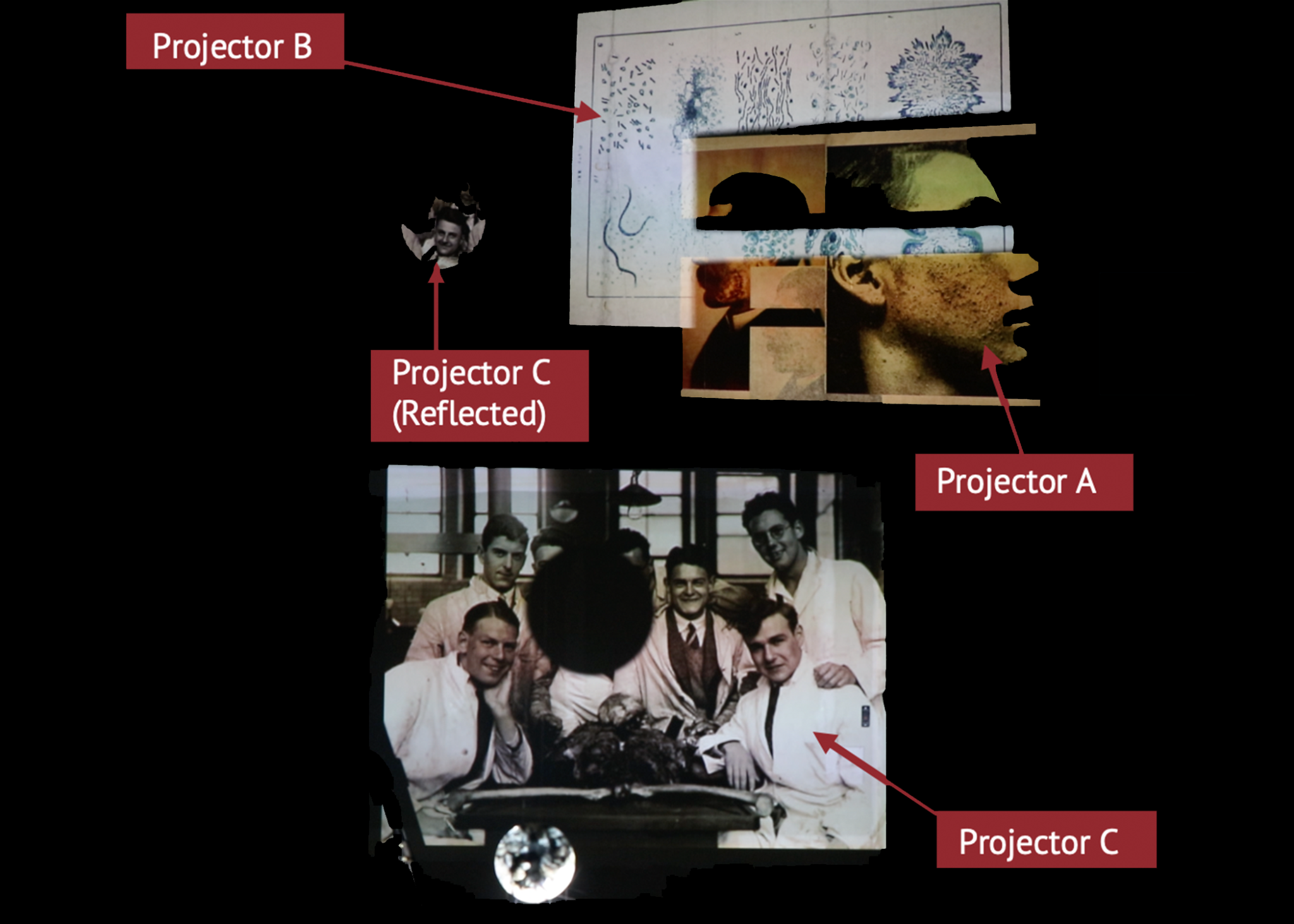

Terminal Imaginaries is an installation art piece of three projectors displaying material from the history of medicine. Each video feed contains material from a different source. Projector A shows photographic material pulled from turn of the century dermatology textbooks. Projector B displays images from dissection manuals and atlases of the human body. And Projector C displays photographs of anatomists posing with their subjects.

VIEW THE TERMINAL IMAGINARIES WEBSITE

Viewers are asked to reflect on these images in the space of either a museum or art gallery. If viewers need additional information, they are given the opportunity to access a website associated with the project through a QR code supplied in the wall text.

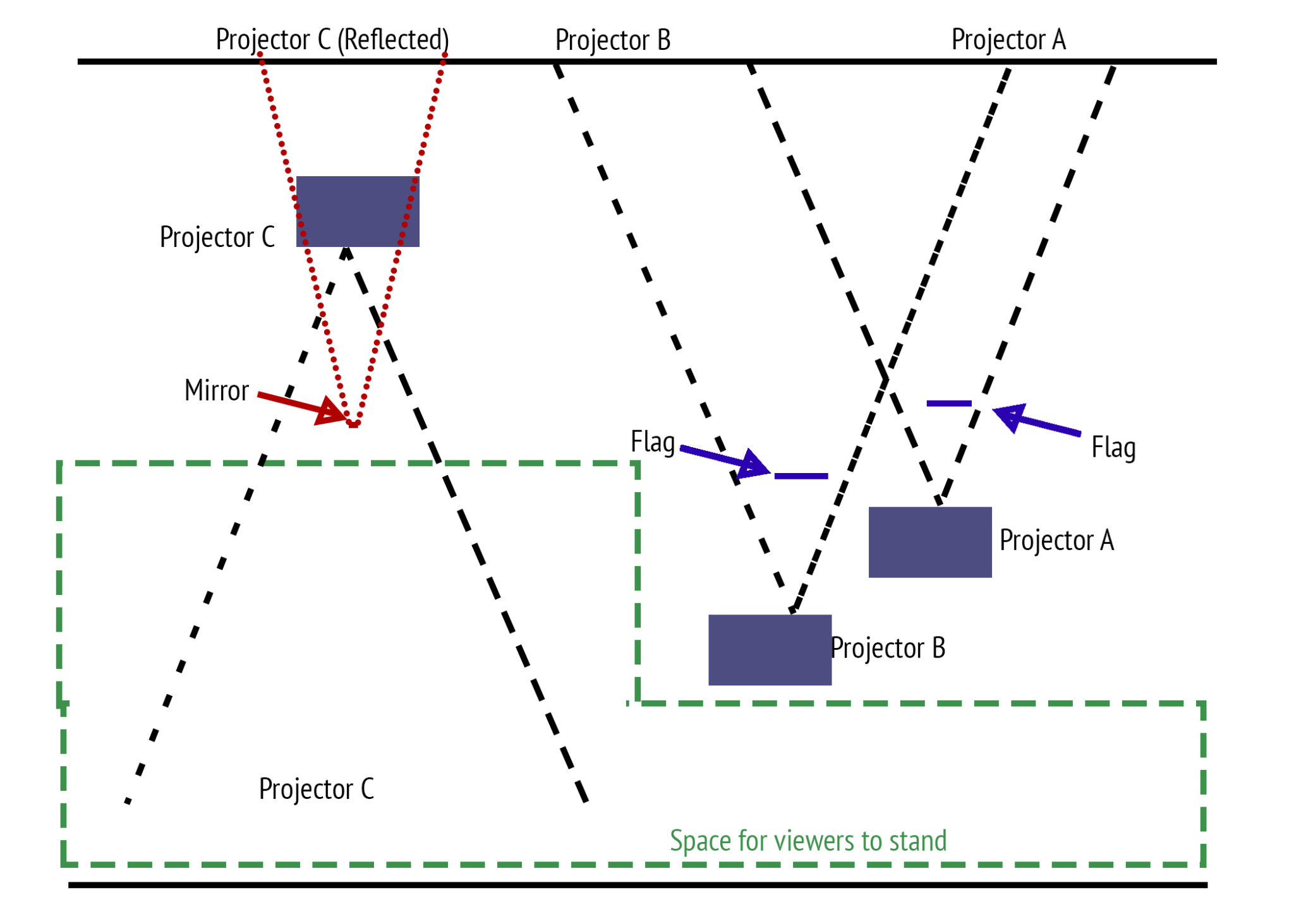

Fig 2. A breakdown of video elements.

Terminal Imaginaries has not been shown in public. It is an exhibit without an audience, and an installation without a site. The necropolitics of the Covid-19 pandemic has obliterated public space, transforming these environs into a field indignant terror—the fear of illness, the intransigence of capital stymieing any transformation that may benefit the health of the public, and the will to let die for an ideology of white supremacist fictions of ‘liberty’.[1] If asked the question (repeated ad nauseum during film school) “who is your audience”, I can only respond: “these days, my audience is dead, dying, or frozen in terror.” Public space has become abject, and the political affordance of spatial politics seem entombed in a mausoleum of idyllic fictions.[2) (After all, if I ask ‘when will I stop having panic attacks in public?’, it prefigures a past moment when I was comfortable in public, and signals to the privilege of my subject position—able bodied, heterosexual, cis male, and white.)

There are two significant data points missing from Terminal Imaginaries: it is an installation with no place to be installed, and whose audience has been cast, like the creature born of Victor Frankenstein, to semi-self-imposed isolation. Site specific art developed in its contemporary form from the Fluxus, minimalism, and performance art movements of the mid-twentieth century. These installations undermined the ideological and institutional frameworks by reconceptualizing the placement of art; it was “not a gesture of hanging the work of art or positioning a sculpture, but an art practice in and of itself.”[3] Cinematic (that is film-based, television based, and projector based) interventions surfaced in relation to these arts movements, as well as the cinematic avant-garde, the discourse of expanded cinema, These works made clear the viewing subject as a “screen subject”, and which made possible new negotiations and engagements with screen technologies.[4]

Fig. 3: The Layout of Terminal Imaginaries

Fig. 3: The Layout of Terminal Imaginaries

I do not think that any reader accessing this essay online, either before, during or after the torrent of Zoom calls, video happy hours, and Animal Crossing island visits, need to be reminded of their position as a screen subject, nor the politics, privilege, and possibilities afforded by the tense (dis)embodied presence these technologies make possible. I choose not to position Terminal Imaginaries in the discourses of newness, of finding something heretofore unseen, or blazing a new avant-gardist trail. Instead, this installation, its impossibility, and the futile contortions of the artist, have made me consider arts-based praxis as an embedded, tactical friction—the impossibility of change, the intransigence of power, leading to a cessation of epistemological validity.

“As the boundaries between illness and health, self and other, became increasingly blurred, I became overwhelmed by nightmarish visions of illness and the compulsion to repeat them on my body. On 23 March 1995, I taped five matches to my right arm and lit them in an attempt to ‘rhyme’ the cumulative effects of Angela’s chemotherapy injections. . . . Within the collaboration, the body’s surface had become a literal and corporeal register of our difference and a site of identification. Yet, the extremity of this act caused a crisis in our collaboration and raised significant questions regarding the trauma of illness, the ambivalence of identification and difference, and the ethics of response and responsibility.

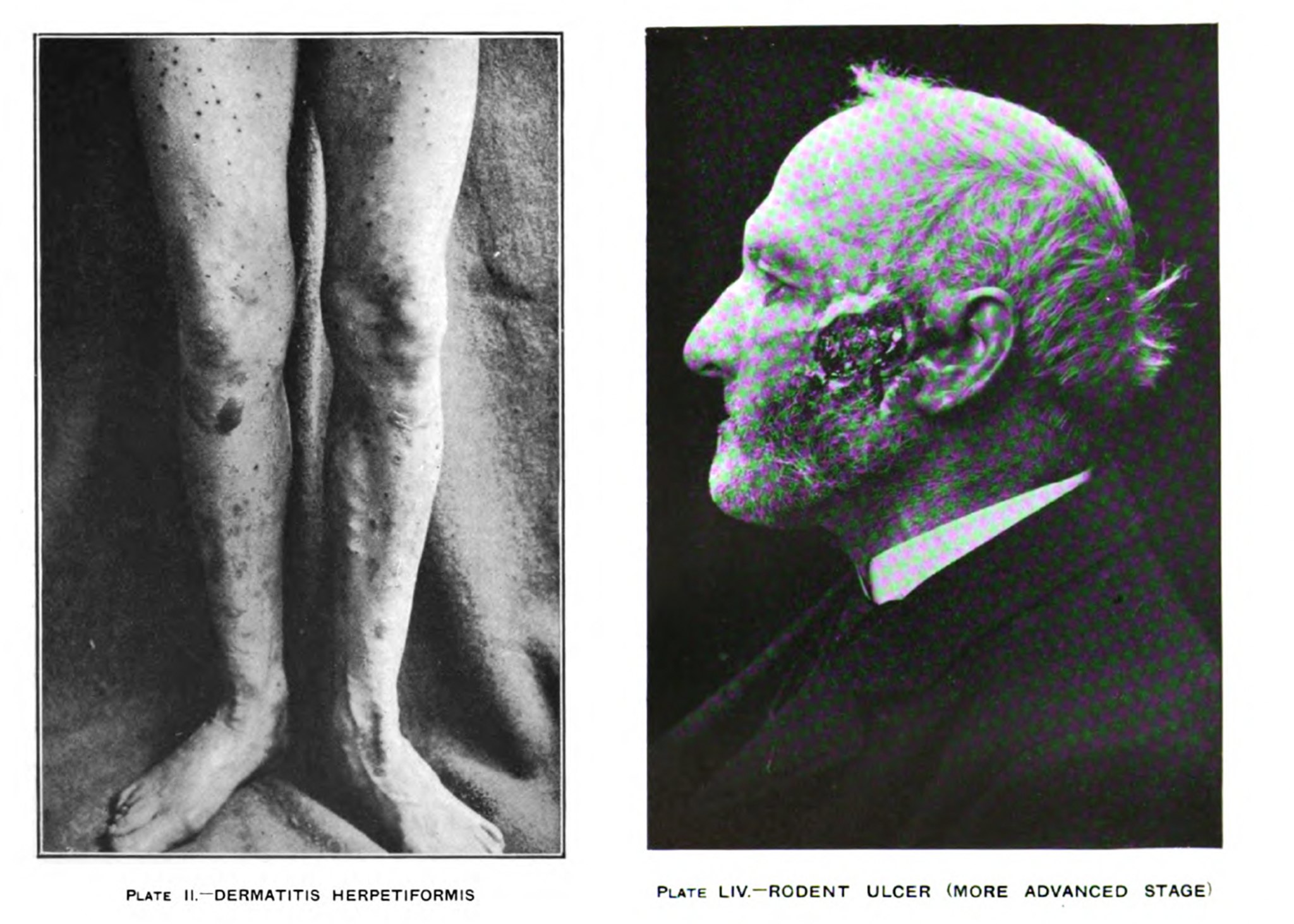

-Tina Takemoto “Wounds”

Terminal Imaginaries came about as a response to dermatological photographs I found in the clinical discourse at the turn of the twentieth century. Skin—a locus of various indexes of race, gender, phenomenological experience, and the would-be container of the modern subject—had been an organizing term to investigate various angles of cultural residue felt upon the surface of the body.[5] In clinical photography, dermatological images afforded a means to show how the “clinical gaze”—Michel Foucault’s term to describe the dehumanizing vision which sees disease of the patient contrasted against the abstract ‘normal’ body—could be repurposed and recaptured through the mechano-chemical apparatus of the camera, while not entirely obliterating the sitting subject’s body.[6] (Common images in the period’s pathological textbooks cut and abstract the body of the sitter, making it impossible to view the human subjected to these practices.) The photographic document placed an individual instance of disease “as a part of a general, generalizable pattern . . . . People change, the pathological portrait seems to say, but the essential features of disease are always the same. In medical portraits, then, the image of disease is an individual in its own right, one whose identity is so stable that it can be transferred unproblematically from one setting to the next.”[7]

Fig. 4. Two images from Sir. Malcolm Morris’ Diseases of the Skin (1909). The left plate displays a visual rhetoric of anatomizing the photographic subject by cutting and framing their body to display the disease in isolation. The right plate displays a more general image where some identifying aspects of the sitter are made viewable.

Fig. 4. Two images from Sir. Malcolm Morris’ Diseases of the Skin (1909). The left plate displays a visual rhetoric of anatomizing the photographic subject by cutting and framing their body to display the disease in isolation. The right plate displays a more general image where some identifying aspects of the sitter are made viewable.

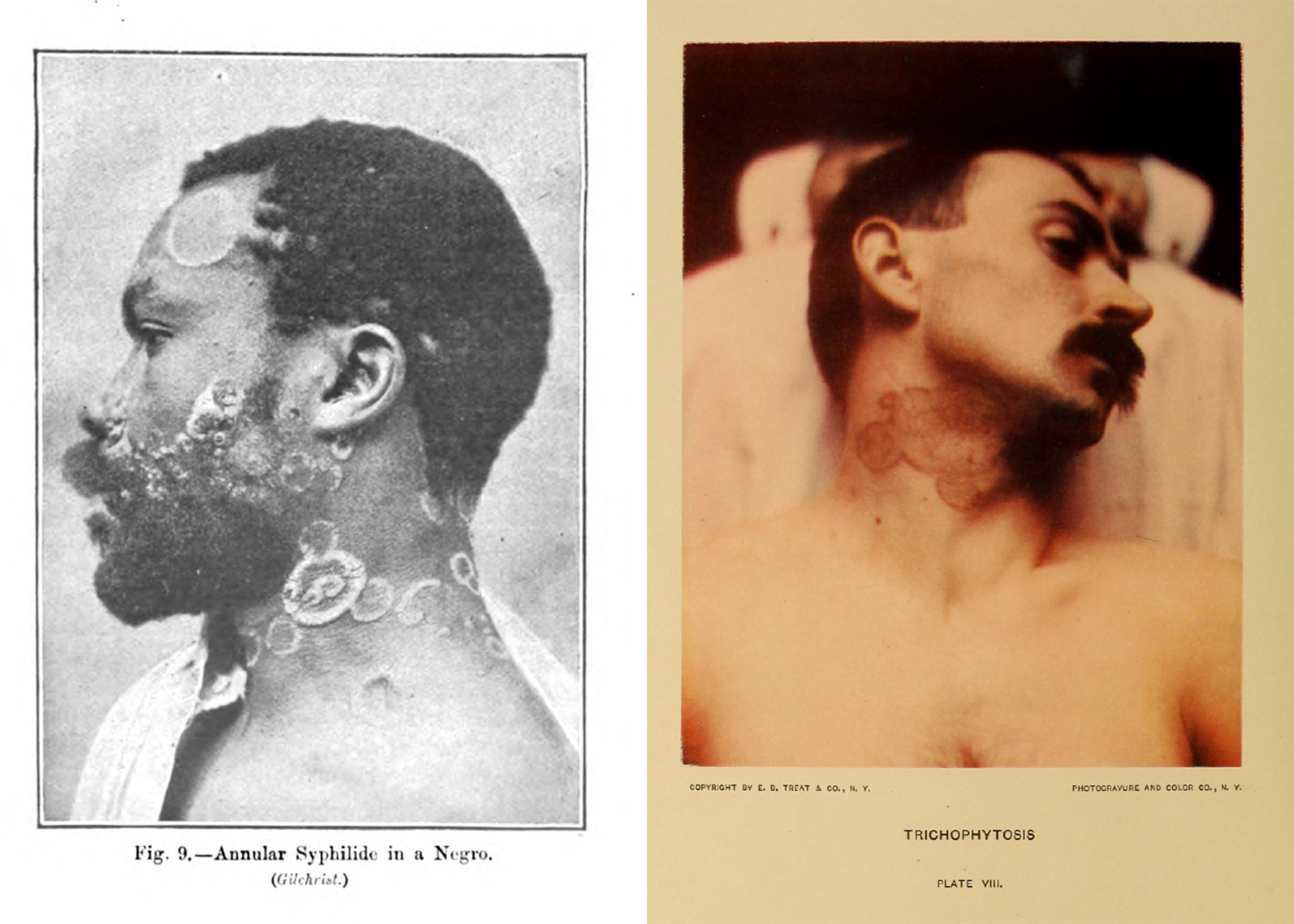

When developing the installation, I thought I could create a space that critically engaged with the history of the clinical photograph. I thought: perhaps, I could use digital projection to remediate and renegotiate the photographs which were so common in medical manuals, textbooks, and atlases. What I found, once I started looking for photographs, was there was not onesingle layer of residual violence caked on these images, but instead myriad compounding and contradictory forms of othering explicit in their visual rhetoric. Yes, these photographs showed a dehumanized, clinical subject, but they also are emblematic of who was subjected to medical study through identifiers of race, gender, and class. Western health has historically been found through the exploitation of poor and othered bodies. As Megan Rosenbloom has argued: “The rich invest in hospitals; the poor get treated; the knowledge gained by the doctors through observation of the poor can be used to better treat the rich. The clinical gaze extended to the way the collective body of the sick was viewed as a commodity.”[8] But there is a secondary, residual discourse: it is not just how the body is pathologized, but also who is made into the subject of disease. Susan Sontag, describing photojournalism’s penchant for uncritically exploiting the aftermaths of post-colonial destabilization, makes this clear: “[these photographs] show a suffering that is outrageous, unjust, and should be repaired. They confirm that this is the sort of thing which happens in that place. The ubiquity of those photographs, and those horrors, cannot help but nourish the belief in the inevitability in the benighted or backward—that is, poor—parts of the world.”[9]

In many ways, Terminal Imaginaries profits on a medical spectacle (charged by the centuries-long European fascination with the memento mori) commonly leveraged by Andreas Vesalias, Frederik Ruysch, John Hunter and Gunther von Hagens (to name only the most famous offenders) to make aesthetic the political corpse. In various times, the corpses of the poor, the criminal, the raced, the gendered, were made both useful and spectacular for the privilege of medical men, their careers, and the institutions that tied themselves to their work.[10] Of note in this regard, (and to contextualize the images which are shown through projector C), the anatomy lab portrait rhymes and capitalizes on another popular photograph in turn of the century photograph: the lynching photograph.[11]

Fig 5. Left: Racial definitions are traded unproblematically in Sir Malcom Morris’ Diseases of the Skin (1909). Right: The white body is deemed normal, and thus needs not be addressed as unique, in William S. Gottheil’s Illustrated Skin Diseases (1906).

Fig 5. Left: Racial definitions are traded unproblematically in Sir Malcom Morris’ Diseases of the Skin (1909). Right: The white body is deemed normal, and thus needs not be addressed as unique, in William S. Gottheil’s Illustrated Skin Diseases (1906).

In light of the violent history of these images I chose to omit certain ones—photographs of children, and photographs of those raced as black and brown. An intentional gap, I feel unequipped and uncertain with how to display the racial violence embedded in the discourses of health.[12] My subject position, the history of the aesthetic corpse, and the open wounds of racial difference leads to my reticence; while remediating these images would bring them into discussion, I would also be spectacularizing the raced subject and then using that object for my own personal, professional gain. I am, of course, ignoring the fact that many of the bodies shown are still raced. Not as the neglected norm of whiteness, but in the historic racial category of Irish and Italian bodies which, by the end of the twentieth century, had been successfully subsumed into America’s white supremacist politics.

I do not know if, by showing the racial character of medical research, I will reveal anything more, so much as reproduce the racial spectacle propagated by America’s white doctors. I could not bring myself to salt the wounds of my colleagues and friends under an ethic of revealing the past. By Sontag’s logic, I would be propagating a discourse of whose body is considered sick, but through omission I occlude the violence obvious in the record.

“The Necrocene ethics of living our dying is, rather, a daily matter of intervention and practice in how to do things with being undone.

-Jill Casid, “Doing things with being undone”

“Censorship is not the mutilation of the show, it is the show. The code is the message. It points to the absolute by hiding it.”

-Chris Marker, Sans Soleil

As I finish this essay, I want to describe arts-based practice as I am trying to conceive it, and shelve for the moment the term “artist” for the term “practitioner”. Partly I want to sidestep the immense cultural baggage associated with the term ‘art’ in favor of thinking of reimagining aesthetic labor. Arts-based practice is a knowledge practice in and of itself.[13] Unlike the unshakable rhetorical authority proclaimed by the sciences, or the subjectively processed potentials afforded by the humanities, arts-based research is productively nebulous. It is performed. It is imperfect. And above all, it is tactical.

I use the term ‘tactical’ to draw on the distinction forwarded by French Catholic theorist Michel de Certeau on the difference between strategy and tactics. The militarist metaphor sees gestures that have the effect toward meaningful social and political gains as being strategic—a march on Washington is strategic, for example—whereas tactical gestures will not, and cannot, function toward meaningful political change. Tactics embrace the futility and ecstasy of gesture that manifests at a micro or nano scale—that of the individual walking in the city, for example.[14] While seemingly unimportant, tactics creates the grounds for epistemic play: it is messy, chaotic, and its products cannot be delimited by hypothetical experimentation. Arts-based practice exists in a mutable discourse, and functions not as a static object, but as a process where aesthetics is but a single (albeit essential) interlocutor. Further, in opposition to other forms of knowledge which rely (explicitly or implicitly) on the technology of hypothesis, arts-based practice does not need to predict its outcomes, so much as examine its aftereffects.

Fig. 7: Still from Projector A using images from The Illustrated Book of Skin Diseases (1906) and Diseases of the Skin (1909).

Fig. 7: Still from Projector A using images from The Illustrated Book of Skin Diseases (1906) and Diseases of the Skin (1909).

The digital technologies upon which Terminal Imaginaries is based affords some instability in regard to its products. Practice based work leverages the process of aesthetic work rather than its products, and, as such, the installation in question should never be considered a static object. Media art and installation art has historically played with and leveraged this immateriality in terms of the concrete art object, and this project takes advantage this instability. It would take about an hour to revise, render, and project a new video feed for any one projector, and it would take about as much time to do the same for the website. As such, Terminal Imaginaries subtly asks for feedback, reflection, and collaboration in whatever form a viewer, colleague or critic might request. While this still foregrounds the practitioner as the final aesthetic decision maker, it displaces and makes possible the criticality of the viewer/spectator. Perhaps this is a minor adjustment in short-circuiting the would-be authority of the aesthetic creator, but it functions to create dialogue between individual actors, rather than the nebulous and unsubstantiated claims of conversation between an abstract public.

While it is great to point to critical, experimental aesthetic work as a balm for fascistoid consumer culture, the reality of this knowledge work cannot be extricated from the ground of its creation.[15]These small interventions are all that are possible. They should not be discounted, but their radicalism should not be over sung. The practitioner, thus, is but another knowledge worker embedded in the networks of power. Their work is vital, but imperfect; longing for change, but futile.

[1] Achille Mbembe. “Necropolitics”, in Necropolitics trans. Steven Corcoran. (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2019), 66-92.

[2] Julia Kristeva. Powers of Horror. An Essay on Abjection. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982); Mikkel Krause Frantzen & Lens Bjering. “Ecology, Capitalism and Waste: From Hyperobject to Hyperabject” Theory Culture & Society 37(6). (2020), 87-109.

[3] Erika Suderberg. “Introduction: On Installation and Site Specificity,” in Space Site Intervention: Situating Installation Art. 5.

[4] Kate Mondloch. Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art. (Minneapolis: University of Minesota Press, 2010), 3-4.

[5] See: Uri McMillan. “Introduction: skin, surface, sensorium,” Women & Performance 28(1). (2018), 1-15; Marc Lafrance. “Skin Studies: Past, Present and Future” Body & Society 24 nos. 1-2 (2018), 3-32; Edouard Glissant. “For Opacity” in Poetics of Relation trans. Betsy Wing. (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1997), 189-194; and Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus. “Surface Reading: An Introduction,” Representations 108(1). (2009), 1-21.

[6] Michel Foucault. The Birth of the Clinic.(New York: Vintage Books, 1994; orig. 1963). See also: Nancy Anderson & Michael R. Dietrich eds. The Educated Eye: Visual Culture and Pedagogy in the Life Sciences. (Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, 2012).

[7] Erin O’Connor. “Camera Medica,” History of Photography 23(3). (1999), 235.

[8] Megan Rosenbloom. Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020), 46.

[9] Susan Sontag. Regarding the Pain of Others. (New York: Farrar, Staus and Giroux, 2003; orig. 1993), 71.

[10] See: Ruth Richardson. Death Dissection and the Destitute. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2000; orig. 1987); Michael Sappol. A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. (Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002); Katherine Park. Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection. (New York: Zone Books, 2006).

[11] Warner, John Harley. “The Aesthetic Grounding of Modern Medicine,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine,LXXXVIII. (2014), 1-47.

[12] See: Harriet A. Washington. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. (New York: Random House, 2006); Robert L. Blakely and Judith M. Harrington. Bones in the Basement: Postmortem Racism in Nineteenth-Century Medical Training. (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997).

[13]Holly Willis. Fast Forward: The Future(s) of the Cinematic Arts. (London & New York: Wallflower Press, 2016).

[14] Michel de Certeau. “General Introduction” in The Practice of Everyday Life trans. Steven Rendall. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988; orig. 1984), xi – xxiv. See also “Walking in the City” in the same volume. 91-110.

I draw this designation after reflecting on the conversation between Stephanie de Boer and Etien Santiago during the Conversations around Materials for Interactions conference hosted at Indiana University. De Boer’s description of the strategic use of commercial screens in Hong Kong assisted in my conceptualization of the arts as tactically practiced in public spaces.

Stephanie de Boer & Etien Santiago. Conversations around materials for interaction conference. (Indiana University, March 7th, 2020).

[15] I am responding to the idealization of avant-garde art as formulated in Max Horkeimer & Theodor Adorno. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception” in Dialectic of Enlightenment. (New York, 1972), 120-167.